Floorplan // Hoja de Sala

Catalogue //Catálogo

Lizzie Zelter

https://www.lizziezelter.com/Lizzie Zelter (b. 1996, New York, NY) is an artist based in San Diego, CA, where she runs Two Rooms, a gallery and project space. She creates paintings and installations with bizarre vantage points of everyday architecture and interior space. Her work explores the micro and macro infrastructure of urban life and the physical structures that produce our built environment. By utilizing reflection and fragmentation in her compositions, she morphs scale and perspective to decontextualize and disguise commonplace objects and places.

Zelter received her MFA in Visual Arts from Columbia University’s School of the Arts in 2022 and a BA in Global Cultural Studies in the Program in Literature at Duke University in 2018. Her work has been exhibited at Untitled Art Miami Beach, Miami, FL with Jane Lombard Gallery, Spring/Break Art Show and Winston Wächter Fine Art in New York, NY, at the Athenaeum Art Center in San Diego, CA, and internationally at Gallery II in Tel Aviv, Israel and Estación Tijuana Libertad, Tijuana BC, Mexico. Wall Plates, at Sala de Espera, in Tijuana BC, Mexico, is her first solo show.

//

Lizzie Zelter (n. 1996, Nueva York, NY) es una artista que vive en San Diego, CA, donde dirige Two Rooms, una galería y espacio para proyectos. Crea pinturas e instalaciones con extraños puntos de vista de la arquitectura cotidiana y el espacio interior. Su trabajo explora la micro y macro infraestructura de la vida urbana y las estructuras físicas que producen nuestro entorno construido. Al utilizar la reflexión y la fragmentación en sus composiciones, transforma la escala y la perspectiva para descontextualizar y disfrazar objetos y lugares comunes.

Zelter recibió su Maestría en Artes Visuales de la Escuela de Artes de la Universidad de Columbia en 2022 y una Licenciatura en Estudios Culturales Globales en el Programa de Literatura de la Universidad de Duke en 2018. Su trabajo se ha exhibido en Untitled Art Miami Beach, Miami, FL con Jane Lombard Gallery, Spring/Break Art Show y Winston Wächter Fine Art en Nueva York, NY, en el Athenaeum Art Center en San Diego, CA, e internacionalmente en Gallery II en Tel Aviv, Israel y Estación Tijuana Libertad, Tijuana BC, México. Wall Plates, en la Sala de Espera, en Tijuana BC, México, es su primera exposición individual.

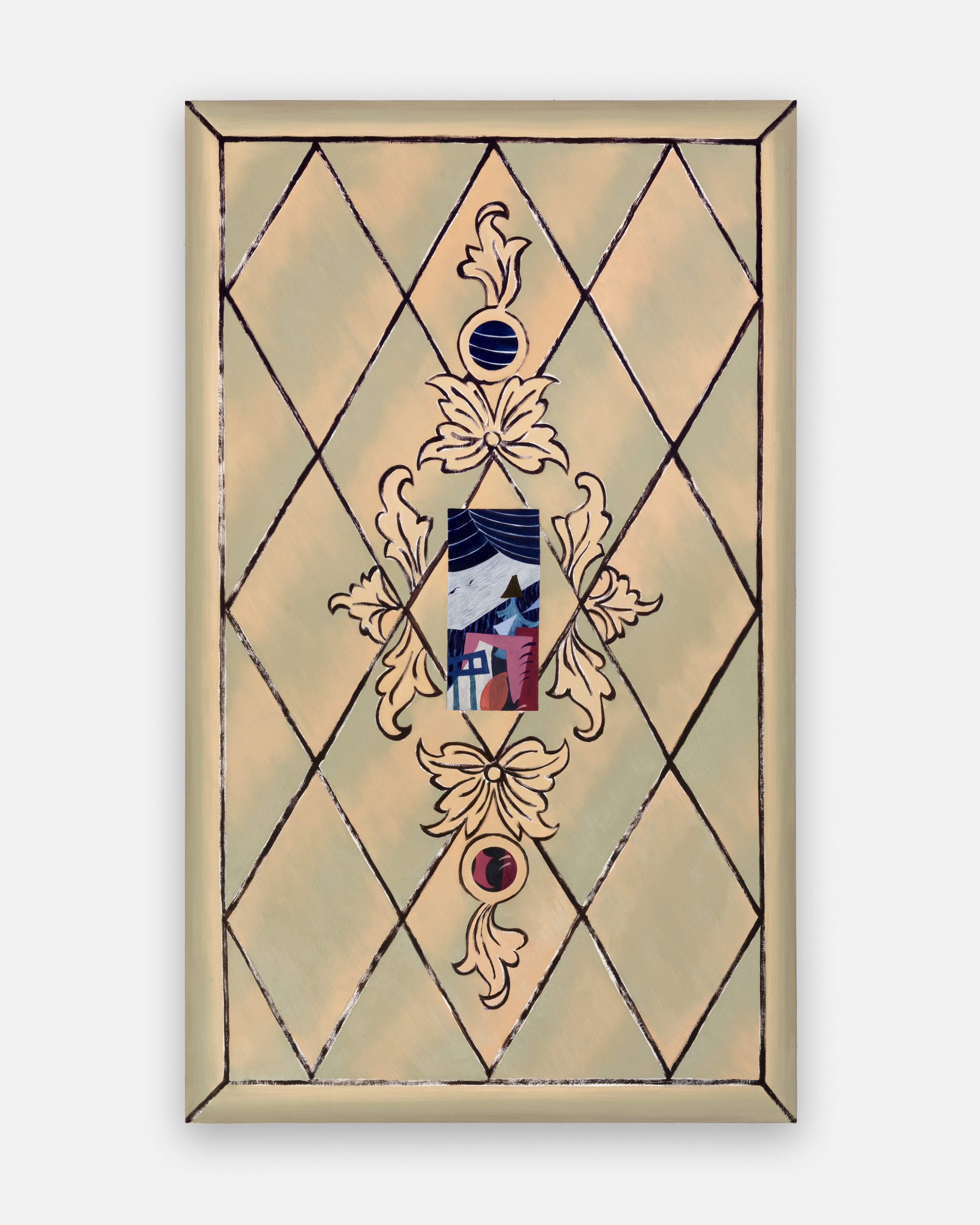

Wall Plates

One day in 2022, I found myself holding up a triple toggle light switch cover and looking through it. I held it vertically, rather than how it is typically affixed to the wall. Visible through the holes was sky, a roof, and trees. Suddenly, a new type of landscape emerged: mostly blocked out with smooth plastic white were three peep holes that showed various snippets of a vague place. Six more holes for screws were portals to additional vantage points.

The paintings in this show are based directly on wall plates I have collected over the past couple years. The dimensions of these canvases, 40 by 24 inches, are the same ratio as the real objects. My work plays with scale as a way to estrange a viewer from what is before them. I often use domestic elements that are both familiar and slightly bizarre, that we see and interact with every day, but may not easily recognize out of context.

Three years ago, I visited the Georgia O’Keeffe museum in Santa Fe, NM. I was drawn to her approach to zooming in and cropping to disguise familiar elements of the natural world. I learned about her relationship with photographer Alfred Stieglitz and their mutual influence on one another’s practices. She became familiar with modern photography and the mechanisms that made this new art form possible. Her exposure to a camera’s viewfinder allowed her to see a delineated sliver of the world while blocking out the rest of the field of vision. Intrigued by this way of seeing, she utilized found animal pelvis bones and other ephemera as viewfinders. The museum displayed a photograph of O’Keeffe in the New Mexico desert holding up a piece of Swiss cheese to her left eye as an impromptu tool. This photograph continued to linger in my mind as a strategy to observe the world.

“Georgia O’Keeffe with the Cheese” echoed an image I had archived from the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. After years of trying, my Hungarian grandmother was only able to escape her native country in the weeks after the Revolution when border security was at its most lenient. Pre-Soviet invasion, Hungary used a flag with horizontal red, white, and green bands and a central coat of arms. With the onset of Soviet rule in 1949, the new coalition government changed the central emblem to a communist coat of arms, with a red star, hammer, and wheat sickle. As protests and fighting broke out, Hungarian revolutionaries cut out the newly imposed emblem as a symbol of resistance.

With their similar dimensions to nation-state flags, these Wall Plates contemplate how we render multifaceted places into flattened representations. They conceal and reveal, leaving spots to peek through.

// Un día de 2022, me encontré sosteniendo la tapa de un interruptor de luz de triple palanca y mirando a través de ella. Lo sostuve verticalmente, en lugar de como normalmente se fija a la pared. A través de los agujeros se veía el cielo, un techo y árboles. De repente, surgió un nuevo tipo de paisaje: en su mayoría bloqueados con plástico blanco liso había tres mirillas que mostraban varios fragmentos de un lugar vago. Seis agujeros más para tornillos eran portales a puntos de vista adicionales.

Las pinturas de esta muestra se basan directamente en placas de pared que he coleccionado durante los últimos dos años. Las dimensiones de estos lienzos, 40 por 24 pulgadas, son las mismas que las de los objetos reales. Mi trabajo juega con la escala como una forma de alejar al espectador de lo que tiene delante. A menudo utilizo elementos domésticos que son a la vez familiares y un poco extraños, que vemos e interactuamos todos los días, pero que tal vez no reconozcamos fácilmente fuera de contexto.

Hace tres años visité el museo Georgia O’Keeffe en Santa Fe, Nuevo México. Me atrajo su enfoque de acercar y recortar para disfrazar elementos familiares del mundo natural. Aprendí sobre su relación con el fotógrafo Alfred Stieglitz y su influencia mutua en las prácticas de cada uno. Se familiarizó con la fotografía moderna y los mecanismos que hicieron posible esta nueva forma de arte. Su exposición al visor de una cámara le permitió ver una porción delineada del mundo mientras bloqueaba el resto del campo de visión. Intrigada por esta forma de ver, utilizó huesos de pelvis de animales encontrados y otros objetos efímeros como visores. El museo exhibió una fotografía de O’Keeffe en el desierto de Nuevo México sosteniendo un trozo de queso suizo en su ojo izquierdo como herramienta improvisada. Esta fotografía siguió rondando en mi mente como una estrategia para observar el mundo.

“Georgia O’Keeffe con el queso” hacía eco de una imagen que había archivado de la Revolución Húngara de 1956. Después de años de intentarlo, mi abuela húngara sólo pudo escapar de su país natal en las semanas posteriores a la Revolución, cuando la seguridad fronteriza era más indulgente. Hungría, antes de la invasión soviética, utilizó una bandera con bandas horizontales rojas, blancas y verdes y un escudo de armas central. Con el inicio del dominio soviético en 1949, el nuevo gobierno de coalición cambió el emblema central por un escudo de armas comunista, con una estrella roja, un martillo y una hoz de trigo. Cuando estallaron las protestas y los combates, los revolucionarios húngaros cortaron el emblema recién impuesto como símbolo de resistencia.

Con sus dimensiones similares a las de las banderas de los estados nacionales, estas placas de pared contemplan cómo convertimos lugares multifacéticos en representaciones aplanadas. Ocultan y revelan, dejando puntos por los que asomarse.

Slice of Swiss

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Fortress

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Inventor of myth

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Unleashed forces

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Pretty for the parlor

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Ghost city

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

The carpet matches the drapes

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Faux bois

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Empty nest

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

If clouds could see

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

Uproot and replant

Oil on canvas

40 x 24 x 1½ in. (101½ x 61 x 4 cm)

2024

*Photos by Daniel Lang